My name is David Abdulah and I am indeed honoured to have been asked by the Girvan family to say a few words at this historic event. I have been a political and labour activist since my days as a student at the St. Augustine campus of the University of the West Indies. That activism has been towards the transformation of our post-colonial society; the economic system of the plantation economy; and the institutions of state that perpetuate that status quo. My passion has been fueled because so very many of our Caribbean people live in “persistent poverty”; are “poor and powerless”. And that is wrong.

My understanding of our Caribbean was shaped when, as a student, I read the works of members of the New World Group: Best, Girvan, Beckford, Millette, Thomas, Brewster, Jefferson, McIntyre, Levitt; to name but a few. The UWI students today do not have New World as required reading; nor are the members of the New World Group teaching any longer. The output generated by and, perhaps even more importantly, the spirit of “Independent Thought” of New World has therefore been largely lost to the generation of today. That is, until this evening’s launch of the Website of New World, which brings to life what James Millette described as “not only an organization, an occurrence, a phase, or a moment in the development of the regional intelligentsia; it was also...the gold standard of Caribbean intellectual development, the source of a uniquely penetrating and perspicacious interpretation of Caribbean intellectual, political, cultural, literary and philosophical development.”

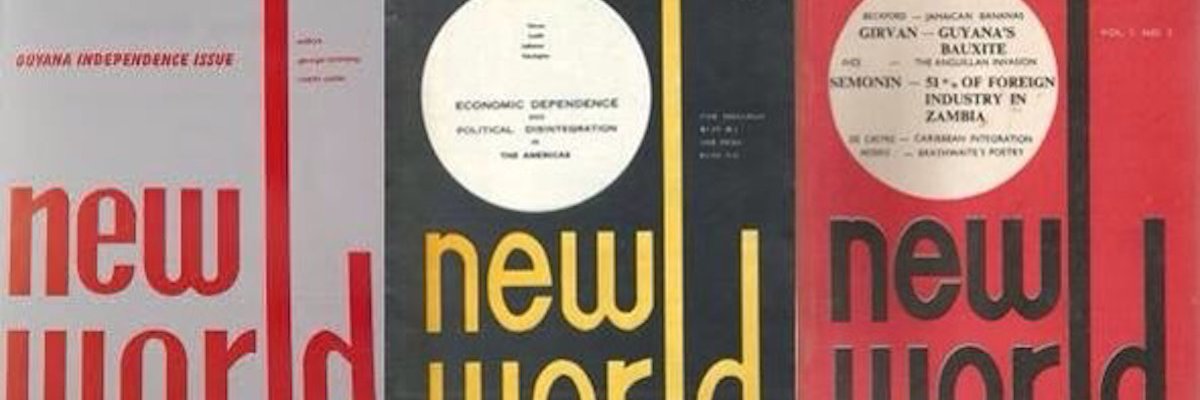

The New World Quarterly was first published in March 1963 in what was then British Guiana. After the first issue the publications continued out of Jamaica until 1972. For part of that time there was also a New World Fortnightly publication which was published in Guyana. Best makes an important point about this brave act of publishing the New World Quarterly – “People of this generation might not understand that, but in those days, to publish anything at all in the West Indies, by a West Indian was a miracle. To see something by you, in black and white, was unheard of. So the real contribution of New World Quarterly was to make to the West Indies, was that it showed all these young scholars that they could see themselves in print and that what they had to say and what they wrote about was valid...it transported the group from being a discussion group into a group that was communicating with a whole fraternity of young West Indian scholars and students”.ii The “discussion group” began in 1960/1 at the Mona campus of the UWI and was known as the West Indian Society for the Study of Social Issues (WISSSI). Lloyd Best was at the centre of this group; with Norman Girvan, Walter Rodney and Orlando Patterson being key members. WISSSI was the forerunner of the New World Group.

But to simply say that Lloyd Best or David DeCaires in Georgetown; or Norman at Mona or James Millette at St. Augustine caused New World to be created is insufficient to our understanding of what brings about change or what propels the formation of activities and organisations that are transformational. I believe that in a society there are key moments of intellectual and artistic creativity which occur concurrently with the economic, social and political ferment of that period. The invention of the steelpan as a musical instrument came at the time when Trinidad was emerging from the anti-colonial general strike and revolt of 1937. In the period just before 1937 there was a flourishing of literary activity with The Beacon Group which included CLR James, Alfred Mendes, Ralph DeBoissiere and Albert Gomes; and just after 1937 there was the emergence of literary and debating groups, one of which was the Why Not group had in its forefront Lloyd Braithwaite; while our rich heritage in dance (Beryl McBurnie in whose theatre we appropriately gather this evening) and music (Edric Connor) came to the fore.

The mass movement of the 30’s and 40’s also generated visionary ideas for the transformation of West Indian societies. These ideas – the agenda for decolonization – were articulated by the region’s labour leaders at the several Conferences of Labour Leaders (British Guiana 1926; Dominica 1932). The most comprehensive agenda was set out in the Resolutions of the November 1938 meeting of the British Guiana and West Indian Labour Congress held in Trinidad.

As Arthur Lewis observed at the time – “It is mainly on the development of this united labour movement that future progress in the West Indies depends...Constitutional reform which will enable it to get into power, is the first aim of the Labour Movement...The Labour Movement is on the march. It has already behind it a history of great achievement in a short space of time. It will make of the West Indies of the future a country where the common man may lead a cultured life in freedom and prosperity”

One important component of the far reaching agenda of the labour movement was the demand for Federation. In fact the 1938 Congress actually prepared and approved a Draft Bill “embodying a constitution for the creation and governance of a Federated West Indies”. The British, however, had their own agenda for Federation and so it was not until 1958 – fully 20 years after the Trinidad Congress –that Federation became a reality, albeit in a very different form from that envisaged by the labour movement of the 30’s. It was almost a natural progression that a group of young intellectuals – students and lecturers – at the then University College of the West Indies at Mona, Jamaica would interrogate the present and future of the West Indies. Norman Girvan puts it most succinctly. “The burning issues of debate were West Indian integration and identity, imperialism, decolonization, racism, socialism, democracy, mass party, and economic development. There was a widespread sense that the emerging postcolonial order was in crisis. The question was – what course should national independence take?”

With the establishment of the University (College) of the West Indies with its single campus at Mona, the conditions were created for students from different parts of the West Indies and with varying academic interests to engage the issues at the precise moment of the rise and fall of the Federation and the move towards formal independence. It was a veritable crucible of ideas. The West Indian intellectuals and their colleagues from outside of the region, beginning with WISSSI and then in New World established the policy framework for the agenda of the mass movement a generation before. In 1938 there did not exist a critical mass of West Indian academics in history, economics, political science, sociology, literature to engage in the research and analysis of our colonial societies and to search for explanations of our condition from the standpoint of our own experiences. In the early 1960’s there was such a critical mass and that generation took up the challenge brilliantly.

New World was a most apt name for many reasons. Best gives one: “We discussed it (the name) at length, it wasn’t arbitrary... And the idea that we had a new civilization in America...runs through the work afterwards. Later on, in terms of North America being colonies of settlement; South America being colonies of conquest and the Caribbean being colonies of exploitation...a new world in America”.v To this I think we should add that establishing New World was pioneering as in the act of publishing; it was visionary as in offering ideas and a programme for the transformation of our societies; and it was brave: it challenged the status quo of colonial society and the institutions of, and the people who held, power. The most important challenge by New World to the status quo was in the realm of ideas and of our understanding of who we are as a people. New World was therefore also revolutionary. Girvan says it well. “independent thought held that the root of the Caribbean’s problems lay in the colonial cast of mind, to epistemic dependency, to flawed conceptualisations based on “imported” formulations. This was true for the economics, the politics, the society and the culture – all elements of an interconnected whole. It followed that the first step in addressing the Caribbean problematique would be to conceptualise our own reality from within. It would mean observing the economy, the society, and the politics without reliance on preconceived models derived from the experience of others. It would mean close study of our own historical experience and locating our reality in the context of that history. It would mean drawing on the insights of writers, artists and other cultural workers, and then and only on that basis, developing concepts and theories that are appropriate to us”.

Is this Website, then, just going to enable students to learn of what some brave intellectuals did 55 years ago? I think not. Our Caribbean condition has not, in essence, changed in those five decades. You see, the problematique remains. Hear Lloyd’s words ring out: “I say that when they (graduates) leave the University of the West Indies they don’t know anything; and I want to say that many of the people working there don’t know anything...I clearly can’t mean that they don’t have plenty information. I clearly can’t mean that they don’t have any intelligence; I clearly can’t mean that they are not doing work, because that would be absurd. So when I say they don’t know anything, I mean that they are unable to hang things together in a way sufficiently coherent to understand the world that they are in”

And let Norman’s ideas come alive again this evening: “the New World mission of intellectual decolonisation is more relevant than ever because intellectual colonization is alive and well and living in Mona and St Augustine and Kingston and Port of Spain. The methods of intellectual colonization are the conditionalities of the international lending agencies and donor countries; their financial surveillance, their technical reports on our education system and our health system and our agricultural policy and public sector reform. The methods are the daily bombardment from the global media, it is scholarships and fellowships and travel grants that do is the favour of assimilating their worldview, and it is consultancies given to scholars where they define terms and we do the work...Are we setting the agenda? Are we questioning the concepts that are handed down to us and adapting them to fit our history and culture and cosmologies and inventing others when none of them fit? Have we lost the boldness and audacity to think for ourselves and invent models of our own? We cannot afford to lose that capacity and I daresay we have not lost it. The question is, do we have the will to exercise it? So the fact that the world has changed since the 1960’s does not mean that it has not also remained the same. We have a different world from the world of New World but it is in many respects the old world that new World opposed”

My generation at St. Augustine were students of Best and Millette. I was lucky to be in places which enabled me to later on become a collaborator with and friend of many of the New World members. Today’s generation does not have that good fortune. What you do have now, however, thanks to technology and the dedication of Jasmine, Alexander, Alatashe, Judy and Kari and their devotion to Norman’s wish, is this Website. Through it you can become acquainted with the wealth of knowledge offered by New World; inspired by the adventure of discovery that “independent thought” creates; and most importantly imbued with the audacity, bravery and boldness to exercise the will to oppose the same old world that New World opposed and thus bring us closer to constructing the Caribbean civilization – our new world in our America – of freedom, prosperity and justice for all, that has been our journey since slavery.